- Don't book a hunt at a sports show, unless you have researched the outfitter before hand.

- Don't be swayed by glossy brochures and slick videos. Those may not signal a bad outfitter, but good and bad outfitters have access to the same marketing companies.

- Don't believe everything that people on a client list say. Marketing an outfitting business is like a lawyer defending a client--accentuating the positive and ignoring the negative. Client lists can be tailored to the desire effect. *nudge, nudge, wink, wink*

- Don't make a deposit on a hunt unless you will be going. Most deposits are non-refundable. Sometimes they will transfer or can be used the following year, but rarely refunded.

Monday, April 27, 2009

Selecting An Outfitter, Part One

Sunday, April 26, 2009

Successful Montana Elk Hunters

Montana Elk Hunter Success Statistics in a Nutshell:

- About 20% of Montana Elk Hunters harvest elk

- About 51-52% of Montana Elk Hunters harvest was antlerless elk (cows and calves)

- From years 1999-2002 Montana Elk Hunters logged about 800,000 hunter days

- That same period each hunter spent about 7 days hunting

- It took 35 to 40 hunter days to harvest one elk

Source: Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks 1999-2002 Executive Summary of Elk Hunting and Harvest Statewide and Regional

If you like to read spreadsheets and crunch numbers, more data is available here.

Those are numbers provided by Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. Numbers and figures from outfitters on public or private land are difficult to obtain, and in many cases may be embellished to suit the specific outfitting business.

The individual hunter is the only one who can measure true success.

The overly optimistic elk hunter should keep in mind that less than 49% of the successful 20% of elk hunters take bulls home. That 49% includes spikes and rag-horn bulls (non-mature 2x2s to 6x6s). The number of Montana Elk Hunters that take home a 6x6 or larger is very small and those that take the “wopper” are an even smaller minority.

In more than 100 years of Boone & Crockett records there is still only one number one—now probably the spider bull from Utah.

It might be fun, or terrifying, to find the number of hunter days expended to harvest the latest number one.

Saturday, April 25, 2009

What Is The Best Type of Elk Hunt?

- Everything is provided

- No car rental

- Experienced guides and operations

- Camp is set up

- Firewood is usually cut and split

- "Everything" is rather subjective. Some outfitters have "valet" service, others have "bare-bones" operations.

- Experienced guides and operations are also subjective. Some outfitters have more experience with construction or computers they used in their former professions than with hunting and outfitting. Young (or old) inexperienced guides may know less than you about elk or the area being hunted.

- Hunts are scheduled to maximize the number of hunters that can be taken in one season. You may have to hunt when you really don't want to. Weather is important.

- Since outfitters try to fill each hunt, you may end up hunting with someone who isn't quite your type. That happens more than writers write about.

- In Montana, non-residents that book with an outfitter get the more expensive guaranteed license, but can only hunt with an outfitter. They can't come back later and hunt on their own.

- Bad things can happen on fully-outfitted hunts, as well as the non-outfitted ones. Go here to read about hunters who got lost in less than 600 yards.

- Cheap

- No set schedule

- If you have the time from work, you could hunt all season or several times that season

- Cheap can get expensive: If you thought you could pack an elk on your back, you may end up hiring an outfitter to pack it out. Emergencies that outfitters (some) can handle may be life-threatening on your own.

- The learning curve for those new to elk hunting or rustic camping is steep. Getting experience on your own can be expensive and life-threatening. For more information on the learning curve go to, "It Really Happened, Really."

- Non-outfitted hunters must buy draw-type licenses. There is no guarantee that you will be drawn.

- In the middle between outfitted and non-outfitted.

- Allow the new hunter/rustic camper a chance to get experience while still under the outfitter's protective umbrella. Most drop camps have camp set up and the outfitter's crew usually takes care of caping, quartering and packing game.

- Day-to-day you are on your own. This can be pro or con. You may learn more on your own, you may not.

- No guaranteed license

- Day-to-day you are still on your own.

Montana Elk Hunting, FAQ

- Statewide about 20% of Montana Elk Hunters are successful. For more information go here.

- Two Most Important Things To Take On An Elk Hunt

- Elk Hunting Binoculars: Don't Break Your Glass

- Knives for Elk Hunters

Thursday, April 23, 2009

Cross Training With Prairie Dogs

If elk hunting were a competitive sport, there would be many articles about “cross training for elk hunting.” Some people actually do treat elk hunting, or any hunting, as a form of competition, but I thumb my nose at them and treat elk hunting as a time of friendship, fellowship and goodwill with my comrades.

The problem with only hunting elk is elk season is just a few months long, and if done right, ends with shooting only one rifle round at one elk each year.

To solve that problem an elk hunter can cross train with other hunting and shooting activities.

In addition to extending hunting opportunities and improving marksmanship, cross training allow people like me to engage in more friendship, fellowship and goodwill with my comrades.

This past week the stars and planets aligned and gave some members of my family a chance to cross train, shoot some prairie dogs and wish my nephew good luck.

My nephew, Jacob Carroll, came home on leave before being deployed to Afghanistan for a 12-month tour with the 82nd Airborne Division. Although a little early for good prairie dog shooting, it provided us an excuse to enjoy Montana’s outdoors. Surprisingly, temps hit the 80s for the first time this year.

Lots of sun and fun.

Dan Clowes instructing his son Austin on shooting procedures.

Dan Clowes instructing his son Austin on shooting procedures.

My brother, Brian Carroll, his son, Jacob, his son-in-law, Dan Clowes, and Brian’s grandson and Dan’s son, Austin Clowes met in Great Falls. We drove north to Big Sandy, Montana and then east to an area south of the Bear Paw Mountains. If you know the story of the Nez Perce Indians you may have heard of the Bear Paws.

The Bear Paws aren’t far from where Nez Perce’s Chief Joseph finally surrendered to the Army, ending the last serious Indian fighting in Montana in 1877.

Dan and Austin Clowes and Jacob and Brian Carroll "sneaking" on some 'dogs.'

Dan and Austin Clowes and Jacob and Brian Carroll "sneaking" on some 'dogs.'

There wasn’t any serious fighting south of the Bear Paws last week. Prairie dogs pups hadn’t yet emerged, and the older, smarter prairie dogs hid in their burrows after only a few shots rang out.

The Carroll crew just moved down the road to the next place we had permission to shoot and engaged another town. Few shots were fired and even fewer dogs were dispatched.

Looking down the working end of a Remington 700VS in .223.

Looking down the working end of a Remington 700VS in .223.

We all had a great time, allowing us to send our best wishes to Jacob before his deployment. The Carroll family seems to always have a connection to the military. During World War II, our paternal grandfather, Arthur Carroll, worked for Bell and Boeing Aircraft. Our father, Craig Carroll was a fighter mechanic in the Air Force in the late 1950s and worked on military missile projects at Vandenburg Air Force Base, California in the 1960s. Brian was a nuclear power plant operator on a fast-attack submarine. Our brother, Michael Carroll, who didn’t go to Big Sandy, was a crew chief on Chinook helicopters, and I was a paratrooper in the Panama Canal Zone.

Besides reaffirming our military heritage, we were able to pass on our hunting ethic to one of the youngest of the Carroll clan, Austin Clowes who is 8-years old. Under watchful eyes he was supervised in safe gun handling and enjoying some of what Montana has to offer.

Austin Clowes with his Ruger 10-22.

Austin Clowes with his Ruger 10-22.

After a long day lying in the sun, we returned to Great Falls got a shower and clean clothes at the Hilton, dinner and a drink at Chili’s and an evening exchanging stories—past and long past.

Our arsenal. Top to bottom: Ruger M77V in .223, Remington 700VS in .223, Ruger M77V in .243, and Thompson Center Encore in 22-250.

Our arsenal. Top to bottom: Ruger M77V in .223, Remington 700VS in .223, Ruger M77V in .243, and Thompson Center Encore in 22-250.

I hope everyone’s week was as memorable as ours.

I wish Jacob Carroll all the luck in the world.

TTFN

Saturday, April 11, 2009

Practice de jour

Over the years the debate has raged over what is the best elk rifle.

For a time, the 220 Swift was heralded as the best rifle known. Its most famous proponent was probably P.O. Ackley. He never said it was the best “elk” rifle, but he devoted pages to the uses of the Swift’s velocity.

When Jack O’Connor promoted the .270 Winchester some flocked, while others ran for the exits.

There probably isn’t a “best” elk rifle.

My favorite rifle for Bull Elk. A sporterized 1903A3 Springfield with a small light 4X scope in 30-06.

My favorite rifle for Bull Elk. A sporterized 1903A3 Springfield with a small light 4X scope in 30-06. I have made about equal one-shot kills on elk with the .270 and the 30-06, shooting 130 grain Core-Lokt, Bronze Points and Silvertips in the .270 and 180 grain Core-Lokt and Silvertips in the ’06. In third and fourth place are a 30-30 and a .300 Winchester Magnum with almost equal successes between those two.

An old Winchester Model 94 in 30-30. Light, handy, lethal.

An old Winchester Model 94 in 30-30. Light, handy, lethal.

In other hunter/writer/expert’s opinions larger calibers are needed. The .338 Winchester Magnum and the 7mm Remington Magnum seem to get a lot of press. Some even declare that the 30-06 is the bare minimum for elk.

I sometimes wonder what the minimum caliber for elk was before 1906, and if the minimum for elk today is an ’06, then what is the minimum for an elephant?

According to Ackley and O’Connor, renowned elephant hunter W. D. M. “Karamojo” Bell, who killed over 800 elephant, used a rather small cartridge for most of his kills. In Ackley’s Handbook for Shooters and Reloaders, Volume I, he says, “For this task did he use the .416 Ridgy? The .450/500? The 600 Nitro Express? Certainly not. He used the 7mm Mauser. [ . . . ] Mr Bell found that the 7mm rifle killed elephants dead—and nothing will kill deader than dead.”

It must be a coincidence that O’Connor’s wife, Eleanor, used the same 7 X 57 Mauser to kill African game, deer and elk.

Using that caliber to make kills on so many different types of game means that Eleanor O’Connor must have been a good marksman . . . um, markswoman . . . hmmm, marksperson . . . Here it is, “Eleanor O’Connor must have been a good hunter.”

A good hunter knows that elk hunting is an individual sport, in some ways like wrestling, and good wrestlers don’t get the edge by buying the best leotard available—THEY PRACTICE.

And, with practice ANY RIFLE is the best rifle for elk.

Instead of commercialized Magnum de jour or Rifle de jour maybe it should be:

Practice de jour.

An elk hunter will never go wrong with a .270/.280/30-06-class rifle.

For more information on The Elk Hunter's Rifle go here, or here.

Time to "Make A Deal!"

If you have been thinking of visiting Montana on an elk or deer hunt with an outfitter, now may be the time to do it.

On Friday, 10 April, I received an email from Neal Whitney, License Bureau Analyst for Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. He said that there were 775 Big Game Combination (outfitter sponsored) and 40 Deer Combination (outfitter sponsored) licenses that had not sold on March 16th.

The Big Game Combination license includes elk, deer A, upland game bird, fishing and conservation licenses. The Deer Combination license includes deer A, upland game bird, fishing and conservation licenses.

These licenses are available to non-resident hunters that book a guided hunt with an outfitter. Drop camps do not apply.

Whitney said that the department will draw general combination licenses and issue the outfitter-sponsored licenses on Monday, 13 April. When that is accomplished any outfitter sponsored applications received after 16 March will be issued.

If you haven’t researched an outfitter that suits your tastes this may interest you.

However, if you have found an outfitter you like, you could use this information to negotiate a better price on a fully guided hunt.

The remaining licenses will be issued first-come, first-serve.

Go here for general license information.

Go here for Nonresident Combo license information.

Go here for the Annual Rule for sale of Nonresident Combination Licenses.

TTFN

Tuesday, April 7, 2009

That One Was Low, Lob Another One, Floyd

The internet has a range of forums devoted to hunters and shooters. Hunters write questions and, then the “experts” answer them. Many of the questions revolve around the “perfect rifle” for game ‘x.’ Or, what is the best rifle for situation ‘y.’

Some of the hunters and many of the experts don’t seem to know what they are talking about.

Here is one recent question. “I need a rifle that will shoot an elk at 600-800 yards. I am favoring the .338 Mag, but some of my friends say the 7mm is best. What is really best?”

Answers were like goose shit—all over the place. It is probably not correct for the expert to answer the question with a more appropriate question to the hunter, “Can YOU shoot and HIT an elk at 600-800 yards?,” but they should.

Let’s question the question in three parts:

What is the average range of an elk kill?

Most elk are taken within 200 yards. Most hunters have difficulty hitting an elk beyond that range. If you hunt in timber, you can’t see 200 yards.

How accurate is the rifle you are buying/using?

The cone of fire from most factor rifles is marginal at 600-800 yards.

What is your ability as a marksman?

Even experience marksman will have a tough time engaging a target at 600-800 yards with the first shot.

Thousand-yard iron sight team match. Roumanian Cup, Camp Perry, Ohio, August 1994. Can you see the targets?

Thousand-yard iron sight team match. Roumanian Cup, Camp Perry, Ohio, August 1994. Can you see the targets?Master-class highpower shooters usually score 197-198 at 600 yards. That means that 17-18 of 20 shots have landed within the 10 ½ inch 10-ring and two shots landed in the 15 inch 9-ring. A person might say, “Great that will kill an elk!”

But that isn’t the whole story. Highpower shooters are shooting an accurized rifle; usually one that has low recoil and have had two sighter shots before moving to record fire. Few of my first sighters are in the ten ring and occasionally, depending on weather conditions, some may be sixes or sevens. The six ring is 46.5 inches at 600 yards and the seven is 34.5 inches.

Additionally, highpower shooters are shooting from a sling-supported prone position, shooting at a KNOWN range, and have been observing wind and weather conditions and possibly how other shooter’s bullets have behaved in them.

Assuming a person’s training is great, they estimate range EXACTLY, have an accurate rifle and FEEL A NEED to lob a bullet at a living BULL ELK more than half-a-mile away, how will their .338 or 7mm perform?

Fine. A .338 loaded with a 250 grain bullet will have about 1900-2000 foot pounds of energy at 600 yards. A 7mm Mag loaded with a 170 (spitzer-type) will have about 1300-1400 foot pounds at that range.

But it brings another problem. If either rifle is zeroed at 300 yards, they will each drop an additional 60 inches (read five feet) at 600 yards. So, the shooter must hold his wobble area five feet over the center of his target.

Thousand-yard any sight match, Fort Lewis, Washington, 1995.

Just for grins, the bullet drop is 287 inches (23 feet) and 242 inches (20 feet) at 1000 yards, respectively. And in both cases energy has dropped off to the point it shouldn’t be used on small deer.

Finally, a ten mile per hour wind from 90 degrees will drift either bullet about two feet at 600 yards. Can you say “Oh, my scope must be off?”

Few people have the bullet, load, rifle, experience, conditions and NEED to shoot at a living animal at 600 yards. I will jump in here and say that I have seen too many elk, deer, bear and others wounded at 200 yards.

Why wound more just to lob lead?

Let's start hunting and quit hoping.

Monday, April 6, 2009

Something's Eatin' My Elk's Nose, And He's Still Here!

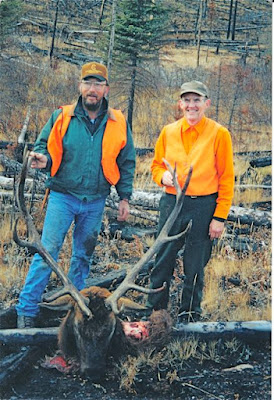

Guide Mike Bouchard and hunter with cape and head. Burnt ground from 2001 Biggs Flat Fire. (2002 photo)

Guide Mike Bouchard and hunter with cape and head. Burnt ground from 2001 Biggs Flat Fire. (2002 photo)Hunting in Montana wilderness areas pose unique challenges.

Many have to do with grizzly bears.

First, and foremost, if you know where a dead, rotting animals is, AVOID IT. Sounds simple but curiosity has killed more than cats.

Second, if you get a bull elk late in the evening, special precautions must be taken. Bulls taken in the evening will most likely not be packed to camp until the next day. If a bear gets on the elk—and it happens frequently—that’s just the way it is.

However, you need to take care of the cape, and/or hide before you leave for the night. It is best if the cape and head are brought to camp. If that can’t be done the head and cape should be hung as high in a tree as possible.

The first thing that a grizzly will gnaw on is the nose. Makes for a strange looking mount.

Any skinning or caping, of elk, deer, bear, etc should be done before leaving in the evening. Not only will bears make a mess of them, but subzero weather can make skinning and caping a chore.

Third, when you return in the morning, come to the elk from the high side and make a good survey of the area before plunging in. If you weren’t there and HE was, it makes the elk HIS property. Grizzlies seem to know that possession is 9/10th of the law.

It is also good to have extra people. One person may not bluff a bear, but a group usually intimidates.

Finally, you should be in good physical shape. Recall the story of the guide and hunter who were running from the grizzly.

Almost out of breath, the hunter looks at the guide and says, “Why are we running, we can’t out run a bear!?”

The guide replies, “I don’t have to outrun the bear.”

TTFN

More Planning

Friday, April 3, 2009

What Do Bull Elk Do? (text)

Bull Elk are almost another species from cow elk and certainly much different from spike elk. As a group all elk graze, sleep, move in herds, breed and avoid hunters, but that is where the similarities end.

Bulls are not only bigger but also slower and lazier than cows or spikes. A well-mounted rider can run a bull into the ground in 200 yards. A well-conditioned young person can walk a big bull into the ground. Really.

My partner Socks the horse on the Cobb Ranch where for several years we move elk to the Sun River Game Range for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks.

My partner Socks the horse on the Cobb Ranch where for several years we move elk to the Sun River Game Range for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks.Bull elk use terrain and timber to leave their predators wondering, “Where did those bulls go?”

Cows are more athletic. Cows enjoy larger herds than bulls.

Spikes are as agile as cows. Actually spikes can be the hardest type of elk to kill. They can take shot after shot and still not go down. The problem that spikes have is they are only a year old and haven’t learned much.

The difference between slower lazier bulls and athletic cows keeps them split all year—except during breeding season. Due to their inexperience and better physical condition (possibly more reasons) spikes are rarely found with bulls of the 5x5 class and larger.

In the accompanying video (here, or here) you can see that they run off when alerted to danger. Then they stop and look, confirming the danger. If they believe it is still present they will move off again. Next, they will do one of two things: get into thick timber and play “mess-around” with the danger; or, they will move about one terrain feature away before stopping, waiting and assessing the situation. I have never seen a bull elk-training manual—they must keep them secret, but the one terrain feature seems to be nearly universal. They may go over a ridge, across a stream or up a hill. Additionally, bulls will almost always try to use elevation to elude a hunter.

Bulls aren’t any smarter than cows. The older cows are probably the smartest of the bunch. Bulls do react differently in the trees. The “messing around” mentioned earlier is typical. While cows will—most of the time—move out in a direction, bulls tend to slow down, take their time and make fishhooks. The denser the timber the smaller the size of the fish hooks.

By making fishhooks bulls can stand quietly and watch the hunter go by, then drift off making another fishhook. Bulls can and will do this all day. It allows them to be lazy and not expend energy.

ELK DO NOT JUST REACT. ELK THINK AND ACT.

That point is important. Many people look at animals as “dumb animals.” Most are not.

I once took gunsmith Albert Turner up the west side of Beartop Mountain (Beartop Lookout is on top) to look for a large bull we had seen the day before. There was about an inch of wet snow. We found his tracks. He was a good 7x7 and had gotten that way by being a tight-ass. I had never seen it before, but this bull was making fishhooks hours before anyone was tracking him. After playing mess-around for nearly half a day, the bull walked through a bunch of smaller bull that had been bedded. Timber, twigs, branches and patches of dark brown hair and light blonde hair and a flurry of legs and flashes of ivory-tipped horns made it impossible to know who was who. An hour after the smaller bulls bolted we were able to find “our” bull’s tracks. What followed was several hours of mess around. He must have been tired of the game, so he finally found a sharp ravine that was filled with 10-12 foot snowbrush. The ravine was only about eight feet wide. He walked downhill along the edge of the snowbrush for a couple hundred yards, turned up the hill—away from the ravine, walked 20 feet into the spruce jungle, and the tracks ended.

West side of Beartop Mountain. The Forest Service Lookout is on the tip of the sharp peak, center left.

It took several minutes to see what he had done. He backed down the hill in his tracks, and then backed up the ravine another 40 feet, and leaped across the ravine. The other side of the ravine—the north side—was a small meadow bathed in sunlight and there was no snow. He had walked up the meadow, entered the timber, turned around and watched us for quite sometime.

I’ve never seen a more nervous bull (or smarter bull). We didn’t get him.

That terrain dictated that I track the bull, but if I am in an area that I know well I usually won’t track a bull. That is playing a silly, exhausting, sometimes daylong game (refer to the silly story above). Although while guiding, I was sometimes forced to track them. It is a guess which way a bull may mess-around, and making a wrong guess can make the guide look inexperienced. Additionally, hunters who hadn’t hunted with me almost always questioned me when I left a good set of bull tracks. On the other hand, some of my most memorable elk experiences have come from leaving the tracks and working bulls in timber. Its even fun in summer when there are no hunters. The grown-ups used to tell me not to chase the elk, but being a kid in the mountains, I sometimes forgot.

If you don’t know the area you have to track them—no way around it.

Whether you track them or not, changing the speed of your stalk works well. Bulls seem to adjust their speed with that of their pursuer. The caveat is that if you get too aggressive you may blow them out without seeing anything but a flash of white rump.

This post is a change for me. I usually don’t talk to people about elk habits. Bulls, cows, calves, spikes are all elk. They all have a special place in my heart. When I talk to people about elk I feel that I am giving away state secrets—sort of a traitor to the species.

Elk--Grand animal of the world.

Thursday, April 2, 2009

American Myth or Mexican Myth

Media Law

. The stylebook is updated once yearly, but they don't change much. If you get one you will notice it is similar to a dictionary. However, it has some querks. It is best to read it over a week or so to learn those querks.

Sights Wobble

First, it is squeezing the trigger while maintaining a good hold.

That brings the question, “What is a good hold?”

Simply put the hold depends on the person; their level of training—both in technical shot execution and physical traits like cardiovascular health; the position—prone, sitting, kneeling, offhand; weather conditions, such as wind, and even position of the moon and stars. The last may seem flippant, but some days we just can’t hold “normally.”

Taken in their entirety, the hold is defined by a wobble area, and the classic wobble area is shaped like a figure-eight on its side, or an infinity sign. The drawing below shows the classic wobble area. Depending on the person and position, the wobble area may look like the next drawing, or it could look more like an oval.

Possible variations of wobble patterns.

With training your wobble area will become more consistent, and smaller. Additional training will also allow YOUR mind to shoot the shot in time with your wobble area.

Until then, it is not important to try to shoot at the center of the wobble. As long as the wobble area aligns with the center of YOUR aiming point YOU have a greater chance of hitting that aiming point, than trying to HIT the center. Essentially, your rifle muzzle is pointed at the center of your wobble area more than at the edges.

Here is a drill that you can do—if you want to improve your shooting:

You will need your UNLOADED hunting rifle, a pencil and paper and an aiming point on a wall. For safety you may wish to remove the bolt. For prone, sitting, kneeling and offhand positions make 5 to 10 holds on your aiming point. Pressing the trigger is not necessary. All you need to do is watch where your front sight—if using iron sights, or your crosshairs track. Watch it for 40 to 60 seconds on each hold, then put the rifle down and draw a representation of your wobble on the paper. When done compare the size and shape of your wobbles.

Competitive shooters sometimes perform this drill repeatedly. Elk Hunters can probably improve if they do it several times each year.

This posting illustrates the marriage of trigger control and the sights. Future posts will move to sights on The Elk Hunter’s Rifle. That is were the importance of a wobble area will become even clearer.

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

One Shot Hunter Program

One Shot Hunter Program